KIM Chandong (Exhibition Planner, Art Critic)

1

Choi Sangchul's work is provocative. Paradoxically, he paints by not painting. He performs other acts of painting like a truth seeker against the contrivance and custom of traditional painting. Most painters aim to paint well, but what does it mean to paint well? Is it the creation of a satisfactory depiction of an object? Or is it the artist’s well-expressed feelings and emotions towards the object? Painting well is a desirable quality built into the history of art. However, Choi turns a blind eye to such great value and devotes himself to not painting well. After the invention of the camera, adequately describing and recreating objects has long been held back. Appropriately expressing an artist's inner sensibility has also become a valuable endeavor under the realm of expressionism or abstract expressionism. Regardless, artists still try to describe and express their work effectively.

The basic discourses of painting related to its very characteristics were devoted to obtaining answers about the nature of art throughout the 20th century. A well-painted figure on canvas is just an illusion, no matter how marvelously it is painted. Additionally, each painting leaves nothing more than paint marks, no matter how well the artist tried to express their emotions within it. This, too, is a trace of the material dimension and has come to be recognized as an illusion unrelated to the reality of emotion. Thus, the essence of painting as painting results in 'flatness as an object'. Minimalism, which simplified the contrived act of painting, seemed to have identified the essence of the work completely in terms of material attributes. However, even if nothing is painted on a plane and simply covered with paint, the plane cannot escape its two-dimensional limit as a reflection of an entity, merely containing an image of something. The artists who investigated these problems realized that the truth of an object could be described as a pure cubic object through a seemingly factory-made, expressionless, three-dimensional geometric structure. They called this manifestation a 'specific object' rather than a work of art.

Choi Sangchul joined the Korean art circle as an artist when so-called 'geometric abstraction' had been popularized during the creation of this modern art discourse. Geometric abstraction was begun as a new style by emerging artists, when the remaining energy of abstract expressionism was exhausted and essentially transformed into an empty style. This geometric formulation consisting of lines, colors, and shapes was a relatively intelligent work compared to past emotional expressions. Due to the shift and influence of the Western ‘hard-edge’, geometric abstraction took on a new style and became popular in most artistic societies. To bring about accurate geometric lines and planes on the canvas, using masking tape became common practice. Many artists preferred this technique that designers used to create sophisticated geometric lines and planes. However, in the mid-1970s, a Korean painting group went mainstream with a white-oriented monochromatic discourse as a result of the introduction of Japanese ‘monoha’ (物派) and the success of the exhibition Five Korean Artists, Five Shades of White (1975) when they were invited to the Tokyo Gallery. Artists were captivated by Taoism or the ‘phenomenology of perception’, which monochromatic paintings and monoha relied on. These Korean artists devoted their work to restoring objects, or things objectified by the subject, to their initial, unrefined state. Attempts to elevate material to a mental level by repeatedly applying monochromatic paint on the canvas without painting anything have since been trending. They tried to build a ‘Korean minimalism’ set apart from Western minimalism by linking the symbolism of white as the ‘spirit of people in white’.

2

On the surface, Choi's work seems to follow the principles of monochromatic painting. His artwork, mainly based in black, stylistically resembles monochromatic paintings and seems to pursue a campaign of inaction rather than artificiality, along with a world of meditation that allows one to empty themself. Monochromatic artists insist on using a single, or similar, color(s) to minimize the contrivance of the work. They also repeat similar actions or patterns of behavior in canvas composition. It is said that through equal, repetitive action, they are freed from their consciousness and attain a spiritual state of perfect selflessness, and as a result, the canvas constructed in this way becomes a spiritual being close to nature. Consequently, monochromatic painting does not simply become an object, but rather a uniquely spiritual object. However, couldn’t it be said that all works—not only monochromatic paintings—are unique objects that blueprint an artist's spirituality? In the case of monochromatic paintings, they try to reach a natural state of emptiness or nothingness through repetitive, impassive actions. However, while working, the artists naturally learn and observe the state of shapes, textures, and colors with their senses, and upon finishing a work, they also reach a point when they are sensibly satisfied. As a result, even though monochromatic artists desire randomness, they must ultimately rely on the consequential perception that has already been acquired and processed by the body. Their pursuit of randomness only results in a contrived conclusion. In addition, it is erroneous to link this with national sentiments such as the 'Korean spirit' symbolized by white. The randomness or natural state of monochromatic painting can ultimately be described as mere ideology.

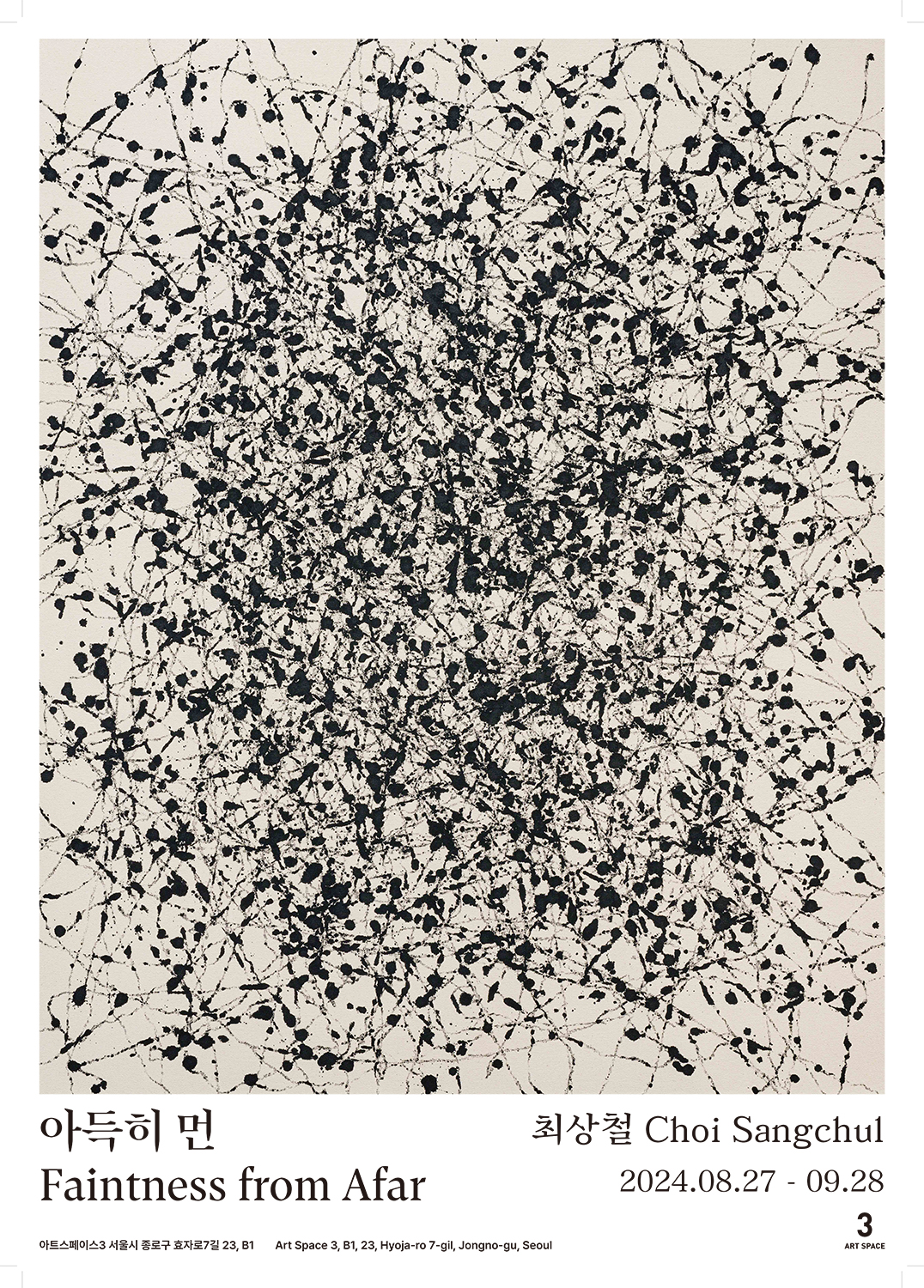

The essence of Choi Sangchul's work comes from his own unique thoughts and techniques set apart from monochromatic painting. He also uses his own tools and techniques in order to remove the inventiveness of the creative process. His best-known technique is the use of 'coincidence'. Used by Western Dadaists and Surrealists to break up rational modernism, coincidence is a classic strategy that Choi uses differently. His coincidence, unlike dépaysements or pun, is connected to in-depth rules. Although coincidence and rules are normally considered contradictory or conflicting concepts, Choi’s work exquisitely harmonizes this contradiction. By developing and utilizing a variety of his own tools, as well as common painting tools such as brushes and pencils, he is able to properly place the paint on canvas. These other tools include rubber seals, small round stones, wires, and strings. He uses these unique tools to leave traces of paint on canvas or paper. The typical steps of his representative work production process are as follows.

First of all, he uses a rubber packing seal with white dots and a stone soaked in black paint. He randomly throws a rubber seal on the canvas, marks the spot when it lands, and rolls the stone from the marked location to record the movement. Each time the stone is rolled, the rubber seal is randomly thrown to determine the starting point. Of course, the artist only needs to keep the canvas at a certain angle so that the stone rolls effectively. It is impossible to create contrived patterns through this kind of process. Sometimes he stands a straight wire with paint vertically at the point where the rubber seal fell, and then naturally lets it go so that there are traces of paint from the fallen wire on the canvas. Wires that are not forced to fall in a specific direction will fall naturally. He also randomly throws a certain length of painted string onto the canvas, which creates markings as it falls. Other techniques of his include leaving traces of paint on paper packaging in the process of packaging objects with painted hands, and handprints left on a white canvas cloth as a result of fixing it to the frame with paint-covered hands. Contrivance is also completely excluded in this process. Additionally, his work includes accidental brush strokes caused by a paint-stained brush being dropped on the canvas at a certain height. His favorite work process of all is to roll a small, round stone dipped in paint onto the canvas to create the work, but since it is not a perfect sphere, it is impossible to predict how the stone will roll. At times he just lets the stone roll off the canvas, and sometimes he installs small barriers around the canvas frame, allowing the stone to hit the walls and create markings by moving freely within the frame, just as a billiard ball does on a billiard table. The artist only tilts the canvas at an appropriate slope so that the stone continues to roll. Unlike the artists of monochromatic paintings, he does not finish his work when the painting reaches a state of formative satisfaction. In order to remove such artificiality, he finishes his work only after repeating the same action 1,000 times. For example, a stone is rolled on the canvas 1,000 times until the work is completed. The number 1,000 symbolizes perfection or completion for the artist. The markings left on his work are those of 1,000 actions. In addition, random methods are used in determining the point or direction where the stone begins to move, such as a lottery system or throwing a small bamboo piece (竹片) that has different sides like a die. In a way, it can be said that the production process contains both mental training and game-like joy.

3

Laozi considered effortless action (無爲) as nature. Choi wants to procure works in a natural state through his work process. It is a pure state of nothingness in which contrivance is excluded. He pursues this pure state before painting and calls it 'mumool (無物)'. ‘Mumool’ is a state of chaos (混沌)—the state of pure nothingness and emptiness, where ‘nothing’ is defined. Is it the essence of world chaos or order? Is it an undefinable darkness or light enlightened by reason? Is it perhaps order in darkness or great chaos masquerading as order? This is an extremely fundamental question that Choi seems to be facing through his work. Countless markings and lines overlap to form layers of countless dots and lines, forming a colored blackness on his canvas. Thus, the black color that governs his canvas is not simply black, but the blackness (玄) of the universe filled with deep chaos. Like a truth seeker, he may be looking for the order of nature inherent in the chaos of a huge circular state.

Pierre-Félix Guattari, a psychoanalyst who co-wrote A Thousand Plateaus (1980) with the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, coined the term 'chaosmose', which synthesizes chaos and cosmos. This concept has generally been offered as another way to resolve the incongruities of capitalism, where chaos represents disorder, uncertainty, and creative potential, and cosmos represents order, structure, and harmony. Within chaosmose, however, chaos and cosmos reciprocate each other’s functions rather than manifest themselves in noncomplementary friction. The concept of chaosmose explains the process of achieving a new order and creation by merging chaos and cosmos together. Art plays a particularly crucial role in this process, opening a way to understand our constantly changing and interactive world. Chaosmose poses a distinctive standard that integrates ecological, social, and mental dimensions. It is the result of hard work—intending to solve the issues we have been aiming for as a civilization (cosmos) and the chaos that still governs our lives. Choi tries to solve the problem based on Taoist or Buddhist thinking rather than Western dichotomous thinking. Objects or subjects are not immutable beings, but constantly changing like the world of Tao (道) or kuu (zero, 空), and all beings are recognized as interdependent, like the concept of ‘paticcasamuppada’ (緣起) in the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. Tao is a concept that includes and harmonizes all beings and phenomena, and is also the fundamental principle of the universe that finds order even among chaos and achieves a new balance through change. ‘無為’ means 'doing nothing' or 'naturalness', emphasizing natural conformity related to the flow of the universe with no artificial intervention. This is similar to the spontaneous and creative process of chaosmose.

4

Choi Sangchul’s intension is to create artwork by completely excluding anything artificial or forced. His canvases, which resemble monochromatic paintings, differ from the existing monochromatic discourse that focuses on contrived repetition to reach a deeper, spiritual level. Additionally, it is unlike ‘monoha’ (派), which seeks communication with objects in their natural, undisturbed state. Choi may be pursuing chaosmose through his work, but of course, he only deals with fundamental problems beyond reality, not directly with social problems. His work leaves no room for a fixed existence or an eternal truth. This is because it emphasizes the change and fluidity of existence. He values natural movement and harmony over superficial interference, believing that all beings are interconnected and exist dependent upon one another. He pursues the cosmos of nature that exists in chaos while pursuing the original essence of chaos.

Inner Chapters of Zhuangzi, The Normal Course for Rulers and Kings introduces a fable called “Chaos’ 7 Orifices”. In this story, there was a creature named Chaos which had no orifices on its body, so they dug 7 orifices for it to breathe, but it died right away. This tale reveals the foolishness of humans projecting their rules and thoughts onto nature. Choi's work may very well be trying to refill the holes that humans once drilled into Chaos. This could allow a once-dead Chaos to revive life-giving activities through internal, natural principles. Isn't this the reason he wants to paint a paradoxical picture without really painting it? The art world seen through Choi’s ‘mumool’ can only be obtained by completely removing artificiality and letting the natural flow...