Hsu Yunghsu (徐永旭, b. 1955) is a leading Taiwanese ceramic sculptor. In 2021, he received the Award for Excellence at the Taiwan Ceramics Awards—hosted by the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum—the most prestigious honor in Taiwan’s ceramic art scene. Renowned for his bold creativity and continuous self-innovation, Hsu is actively reshaping the history of Taiwanese ceramic art. Based in Tainan, Hsu has gained international recognition, exhibiting his work in the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, and across Asia, including Japan, China, and Singapore. While this exhibition at Art Space 3 marks his first solo show in Korea, he is already well known among Korean ceramic artists, having been invited to participate in Korea’s Ceramic Sculpture seminars several times since 2000.

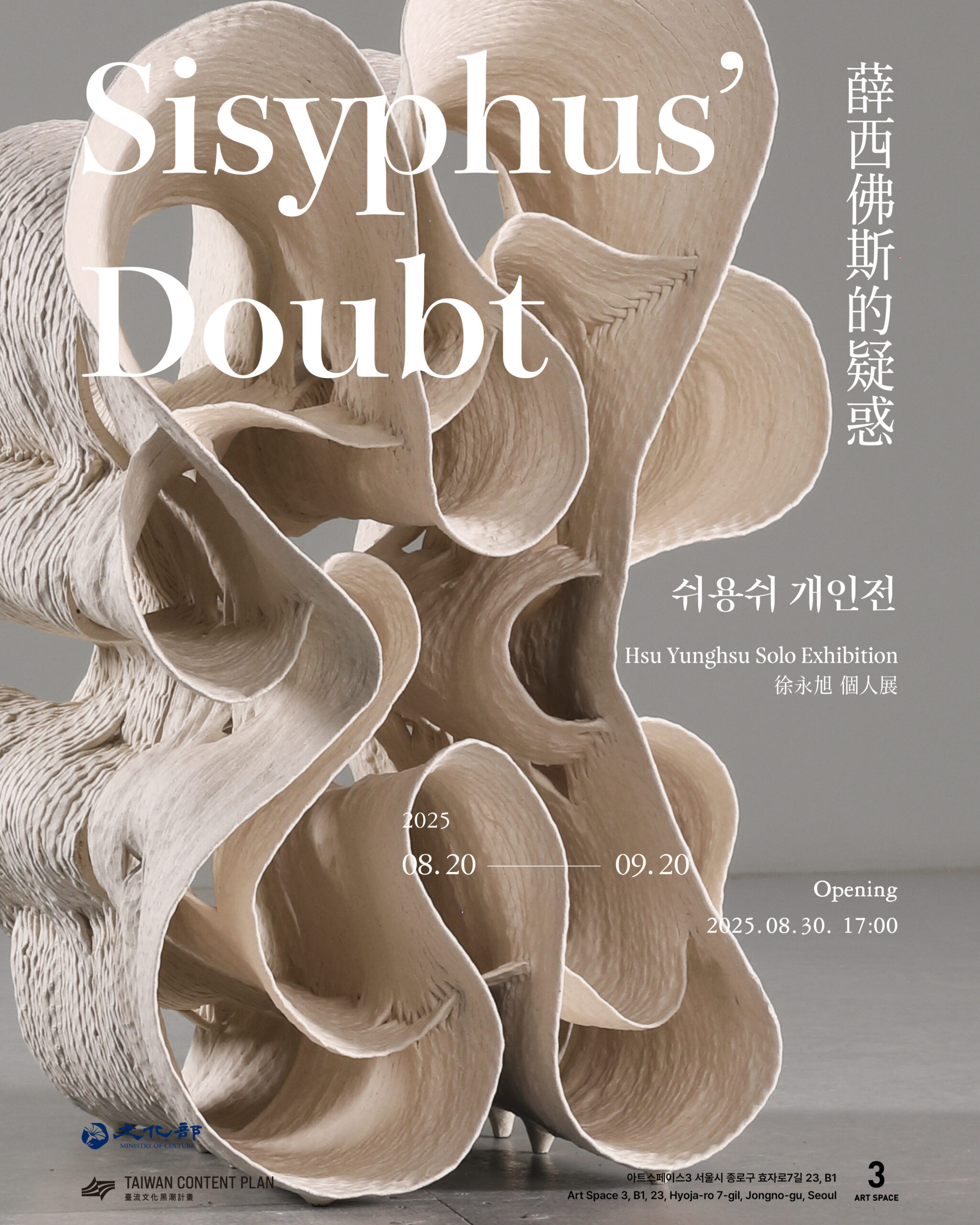

The ceramic sculptures, rendered in monochromatic tones of bright milky white and deep brown, appear so delicate and pliable that it's hard to believe they are made of clay. The usual sense of weight associated with earth is absent; instead, the pieces seem to hold and even emit light. While the organic forms create a striking visual impact, the works themselves are remarkably thin, allowing light to seep through tiny perforations in their surfaces and illuminate their interiors. Entirely hand-built without the use of tools, each piece carries a subtle tactility and vulnerability. Traces of the artist’s hands—finger marks and pressed impressions—remain visible on the surface. In works shaped by the repetitive pressing of fingertips, one senses not only the passage of time and the performative process, but also a quiet poeticism reminiscent of the dot paintings of Whanki Kim (1913–1974), such as Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again?(1970) This tactile expression, emphasizing the raw physicality of clay through the artist’s direct touch, encapsulates Hsu’s aesthetics and philosophy and reveals a bodily presence that transcends mere form-making.

Like a Marathoner, or Like a Musician

In middle school, Hsu Yunghsu showed a natural talent for art, but he initially pursued a different path, joining the track team with dreams of becoming a marathon runner. He trained rigorously and hoped to enter high school on a state-funded athletic scholarship. However, an injury just before the qualifying exam forced him to abandon that dream. Rather than being a setback, this early experience of disappointment seems to have become a vital source of strength and inspiration in his artistic journey. Nothing in Hsu’s life appears to have been wasted, the discipline, endurance, and patience he developed as a long-distance runner now resonate through his art. At 70, he remains energetic—he still enjoys running and devotes himself fully to his studio practice. Beyond hand-building his sculptures, Hsu personally oversees every stage that affects the outcome: from the drying period before firing to the airflow and temperature fluctuations inside the kiln. Not only does he strive to achieve the precise results he envisions, but he also takes on the physically demanding tasks of transporting and installing his large-scale works himself. His artistic process is as much a performance of persistence as it is one of creation.

Hsu Yunghsu became a ceramic sculptor at the age of 40. After giving up his dream of becoming a track-and-field athlete, he enrolled in a teachers’ college and became an elementary school teacher. While teaching, he studied the guzheng (Chinese zither) in his spare time and eventually became skilled enough to hold several recitals. (When our group visited his studio in May 2025, he even took out his guzheng and played a piece for us.) However, the sudden death of an acquaintance prompted him to reflect deeply on life and health. This turning point led him to reevaluate his path and, in 1987, he opened a pottery studio in pursuit of a more authentic life. Although he received brief guidance from a ceramic expert, Hsu was largely self-taught, studying ceramic art through books and independent practice. By the early 1990s, he had moved beyond functional ceramics and began exploring ceramic sculpture as a form of pure artistic expression, gradually developing his own unique style. In 1995 alone, he won seven awards. By 1998, he made the bold decision to leave his teaching career entirely to dedicate himself to ceramic sculpture. The following year, in 1999, he held his first solo exhibition as a full-time artist, firmly establishing his name within the ceramic sculpture community.

The evolution of Hsu Yunghsu’s work mirrors the dynamic arc of his life, and his artistic journey can largely be divided into two major phases. The first phase began when he entered the world of pottery and, about five years later, transformed into a ceramic sculpture artist. During this period, he primarily created figurative works based on the human form. His focus was often the dancing body, which he abstracted into organic, flowing shapes. These works, typically rendered in dark brown stoneware clay, sometimes featured added color on the surface. This phase evokes the spirit of Henry Moore’s(1898-1986) interpretations of the human figure—especially in the organic abstraction of the body and its spatial presence. Hsu’s recurring motif of the dancing body also seems to reflect his personal experience as a guzheng performer. In addition, he also produced works that incorporated mythological references and conveyed social commentary.

The second phase of his work began around 2004, when his focus shifted from human-centered figurative art to abstraction. He began titling his works only with the year of their creation, reflecting a move away from conveying specific topics or messages and signaling a deeper turn inward. In his 50s, he sought to explore metaphysical aesthetics and insights beyond material form, using clay as his primary medium. The A Play of Soil series, which he began in 2005, might seem like a continuation of his earlier phase—especially with the use of the word ‘play’—but it actually marked a new direction. Through this series, he investigated the possibilities of pottery by emphasizing both the characteristics and the limitations of soil as a material. This exploration led to the creation of large-scale works made with remarkably thin clay. Around this time, he also made the unusual and admirable decision to return to graduate school—not as a teacher, but as a student. For an established artist nearing 50, this choice reflected a deep commitment to his practice. During his graduate studies, he engaged seriously with art philosophy and aesthetics, incorporating deeper reflection and critical inquiry into his creative process.

In the first half of 2004, he gained valuable experience as a residency artist at the College of the Ozarks in Missouri. He continued his residencies at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in New York in 2005 and at California State University, Long Beach in 2007. While in the U.S. in 2005, he was deeply impressed by Richard Serra’s(1938-2024) large-scale steel plate installations at Dia:Beacon. The encounter prompted him to reflect on fundamental questions regarding the relationship between sculpture, space, and sensory perception.

The Physicality of Hsu Yunghsu’s Ceramic Sculpture

The Seoul exhibition presents approximately 20 works created over the past decade. Characterized by their monochromatic surfaces and distinctive matière, these sculptures are formed entirely by the artist’s fingertips. Hsu uses two basic techniques that are primitive and directly capture his physicality. First, he rubs a lump of clay by hand to shape a thin, concave ‘unit’ approximately 0.5 cm thick. These forms may evoke associations with bird nests or oyster shells, yet their organic nature resists any direct identification with specific natural objects, allowing viewers to project a wide range of images. The origin of this technique traces back to a life-altering event: a car accident shortly after his return from the United States in 2005. This traumatic experience brought him face-to-face with the fragile boundary between life and death. The lingering psychological impact of that moment weighed heavily on him, and in the aftermath, he found emotional release and calm in the repetitive action of shaping clay with his hands. This process became a new creative method grounded in physical sensation and bodily movement. By freely combining these delicate and lightweight units, Hsu is able to construct three-dimensional forms that push the boundaries of what is physically possible in ceramic art. The resulting installation works vary in structure—some rest on the gallery floor, while others are mounted on walls like relieves, or others can also be suspended in space using strong, transparent fluorocarbon lines.

Another method Hsu uses is the coiling technique. He rolls the clay into long, thin strips and presses them one by one with his fingertips to shape the form as desired. Although this process is slower than using a potter’s wheel, it allows for greater control, enabling the artist to create complex shapes that maintain their structure even at a large scale. This technique reduces the risk of collapse or cracking—issues commonly associated with clay work. Such problems are especially likely to arise when creating thin yet large-scale sculptures like those Hsu produces, and he has addressed them by relying on this fundamental ceramic technique. In addition, he researches clays from around the world and selects types that are as lightweight as possible while remaining strong after firing. As a result, his unglazed clay works become sturdy enough to endure not only indoor conditions but also outdoor environments, making it possible to install them outside buildings and in open spaces such as parks.

The artist’s physicality is embedded in the working process described above. His physical condition at the time of creation leaves visible traces on the work, as the flexible nature of clay responds directly to his movements. Through this interaction between body and material, the resulting form is not seen as a finished state, but as a process—one that captures and contains the passage of time.

From the Artist’s Physicality to the Viewers’

Works created by pressing flexible clay with the fingertips retain and preserve the artist’s actions. Because clay is highly responsive to human touch, even the simplest, most repetitive gestures capture not only the imprint of fingerprints but also the intuition, emotion, energy, and physical condition of the body at the time of making. In particular, when working in a primitive manner—hand-mixing clay without the aid of tools, as Hsu Yunghsu does—each movement of the artist’s hand is recorded exactly as it is. Both his conscious intention and his unconscious state, including his emotions, are imprinted directly into the work. Hsu repeats the same motion hundreds or even thousands of times in a day. Yet no two gestures are ever exactly the same; subtle differences emerge because each moment is shaped by a unique mix of thought, feeling, emotion, physical force, and energy. For this reason, Hsu has described all of his works as ‘self-portraits.’ As he once stated, “For me, sculpture is a way to check my body and senses every day. I change through repetition and go further in repetition.”

The reason why Hsu Yunghsu rarely uses glaze in his pottery is that he tries to exclude the accidental effects of glaze, but also because glaze erases the physical traces of the artist. Hsu wants to vividly capture the movement of his fingers, like his breath—that is, the press marks, fingerprints, microscopic cracks caused by finger pressure, and the rough texture of the clay. Despite the physical demands and limitations of working with clay, Hsu continues to use it as his primary medium because it allows for a more direct expression of physicality than any other material. However, the physicality Hsu emphasizes is not limited to his own body. Since the pedestal is either removed entirely or kept very low, the viewer also experiences the work physically. In other words, it encourages viewers to have a spatial and time-based experience by looking at and moving around the work, departing from the contemplative attitude of viewing it only from the front.

Hsu Yunghsu came to value the direct physical experience of viewers after being deeply moved by Serra’s Torqued Ellipse I(1996), permanently installed at Dia:Beacon. Serra, who emphasized physicality as a response to conceptual art, created work meant to be appreciated in specific spaces—visual art that engages viewers through direct, bodily experience. Hsu encountered an entirely new kind of physicality in Serra’s work: the tension he felt while walking between the tilted steel plates, the sound of his own footsteps echoing, and the glimpse of the sky (or ceiling) from within the enclosed space. This experience of art that is not merely seen but physically felt was a profound challenge for Hsu. Inspired by this, he began to gradually expand the scale of his own work, with the expectation that viewers might enter the space of the sculpture and have a physical experience distinct from that of daily life. His pieces, through the tension of their delicate, subtle matière and ceramic material, draw viewers into a heightened state of attention.

Ceramic Sculpture as a Performative Act

In today's art world, digital technology, artificial intelligence, mechanical representation, and the notion of 'dematerialization' have become dominant discourses. Hsu Yunghsu’s ceramic sculpture works appear to stand in stark contrast to these trends. Rejecting mechanical processes and modern technological methods, his entirely hand-made approach and the materiality of ceramics evoke comparisons to ancient dogū. The repetitive hand movements involved are pure physical labor, and the continuous motion of his fingers seems to push the boundaries of his physical endurance. One critic compared Hsu’s repetitive actions to Sisyphus ‘rolling a boulder uphill.’ In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus presents the absurdity of human existence through the figure of Sisyphus, who endlessly and meaninglessly repeats the act of pushing a boulder upward. Yet, Camus saw in this very absurdity a form of freedom and resistance, suggesting that embracing the lack of inherent meaning is both the human condition and fate, ultimately, the dignity of existence. With his fingers tightly wrapped in elastic bandages, Hsu Yunghsu continues to create his works through the movement of his fingers. This repetitive motion is not merely labor or meaningless repetition, but an ontological awakening as an artist. He immerses himself in his work through the repeated actions of pressing, pushing, layering, and connecting clay with his fingers. The resulting pieces, born from this deep immersion, embody the artist’s time and labor, his experimentation and challenges, his sweat, and a disciplined practice of silence. Hsu Yunghsu creates works that express his will to create and his physical presence through the most primitive materials and methods. He hopes that viewers will not simply see the work, but will feel and breathe with it.

Yisoon KIM (Former Professor at Hongik University /Art Historian)