Sangyong Shim

(Professor, Seoul National University; Director, Seoul National University Museum of Art)

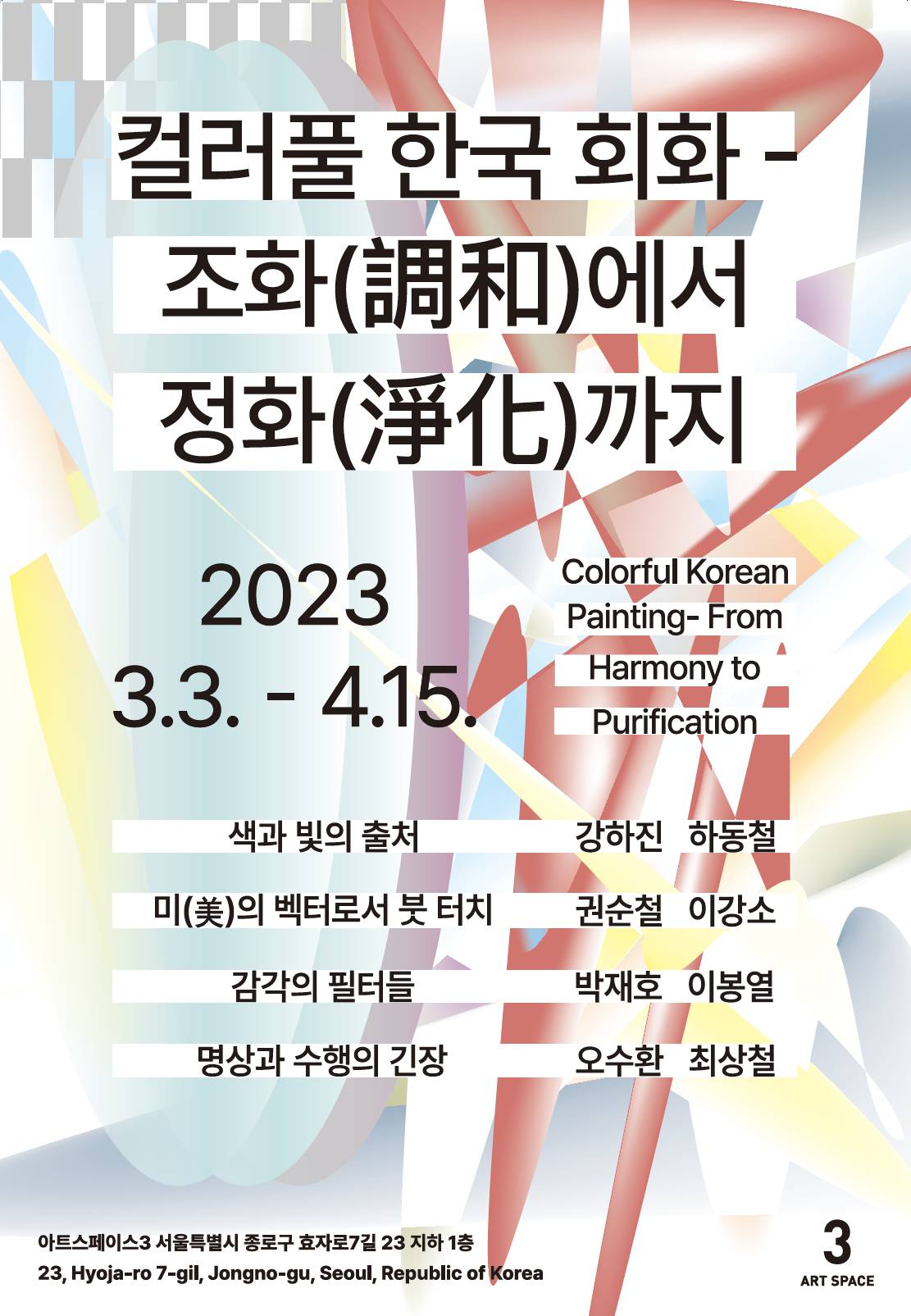

1. Why Colorful Korean Painting?

Life and Art of Eight Different Artists in Eight Different Colors

The eight artists from the exhibition Colorful Korean Painting have passed through the same period of history. Except for Bongreal Lee, who was born in 1937, it's not too much to say the rest of the artists were born right around the national liberation of Korea. "Liberation: freeing oneself from imprisonment, oppression, or restraint." What other term can be more beautiful or more aesthetic than this? In addition to the fact that all of those artists have laid the foundation for the history of painting in Korea, which was liberated in 1945, there is surely a fair amount of contemporaries. Similarly, they become not representatives of history, but history becomes a representative of them.

Eight artists' journeys of life and attitudes toward art certainly have their personal colors and shades. Although the distinction between abstract painting and representational painting isn't largely meaningful, everyone except Sun-cheol Kwun is an abstract artist in their form. However, Sun-cheol Kwun's paintings are seemingly abstract enough. In addition, even if they all fall into the same category of abstract painting, each aesthetic orientation is as different as the gap between the representational and the abstract, so the harmony is truly wonderful.

Definition of 'Colorful' in the Context of Korean Art History

'Monochrome' shouldn't be the aesthetic terminology that represents Korea. It stems from disregard for and insensitivity to the ever-changing charm of Korean art that resembles the multi-colored fairy pitta. At its foundation, we can witness an apparent misreading of Korean abstract painting history. Also, it was misread due to a hastily-created formula within the incorporation of the commodity economy and the rigid reading of our art at war's end. Because of the penetration of neoliberal knowledge tendencies, which claims to be a tool for spreading so-called beneficial knowledge, even reading art was not done properly within the formative (signifiant), aesthetic (signifié) level, and the independence we have achieved has not been read properly.

This is the case for abstract art reading in the 1970s and 80s. The concept of 'abstract' was neither only a distant utopia nor a constant push to disconnect from daily life, but it was considered merely as an illustration of noble and pure ideas. Even if they don't explain each and every meaning, the abstract world is not all difficult. It is not just a byproduct of elitism, as is often said. It's hard for this world to be a diamond in the rough for everyone, but even in this world, everything including feeling (sentiment), admiring (rhythm) and discovering (meaning and metaphor) is possible. Look at the eight worlds in the exhibition Colorful Korean Painting. Even in what seems most distant among them, the attitude of perceiving the world and reflecting on oneself are echoed in a colorful way and in a complex curve, not in a linear orbit.

The Grace of the List

There isn't one consistent perspective, a single descriptive belief, or aesthetic attitude that penetrates these eight worlds. Yet what a relief this categorization failed! We'd rather call it grace ―grace that comes from staying away from the obsession for categorization. Within this grace I encounter these worlds as individual entities, not as processed social status or images―the objects of reading or research, claims, alibis, or evidence. If it were not for grace, it would be impossible to meet them in the raw, escaping the arbitration, intervention of concepts, and cowardly shields of classification and categorization.

Consider the following example: Bongreal Lee won the Recommended Artist Award (1972) at Gukjeon and served as a Gukjeon judge. To Hajin Kang, Gukjeon was an extension of "politics of an art society without principles and grammar." Even though there are differences between the two artists' paths, those two names are equally precious in the monument that Korean art has achieved. Korean art is way beyond the dichotomy between Gukjeon and non-Gukjeon or the division of the left and right wing, thanks to the artists' awakening consciousness.

Consider another example: Dongchul Ha's geometric abstraction, which looks cold and neutral enough, moves back and forth in between the flower bier (the representation of his father's death) and the illusion of mysterious and transcendent light. Sun-cheol Kwun's path was seeking to build up the heated expressions that derived from the suffering land and its people, the most Koreanized element. Unbeknownst to him, that path gravitated to the face of Jesus. Abstraction and conception, and modernity and the people, both of these dichotomies are meaningless, unnecessary, and above all, inhumane.

Art should be a way to open our senses, and to meet, experience and enjoy it, free from the temptation of categorization. Since it's not derived from my typical reasoning, these eight lists shake me even harder to awaken me. Most often, 'ah-ha' moments come through waiting rather than effort. The truth always comes in the form of a meeting, not an answer. Only such a moment of meeting makes us step down from the throne of the foolishness, being satisfied with clumsy answers, and return to the position of the humble questioner.

Within the Context of Korean Art History: A Metaphor of Grafting

It is safe to say that the modern history of Korean art started as a grafted version of Western art. The meaning of 'graft' is by no means simple. A pain from amputation already exists where it is grafted, and young branches, for example, which sprout from a graft, grow with the wound inside their chests. Proper grafting requires more than just supporting with a stick or tying with a string. The most important factor in the grafting process is whether the sap can be delivered from the root soon after grafting, which is more crucial than the main branches. According to Slavoj Zizek, it is no different from the success of a revolution being decided by the people's support the day after. Similarly, grafting is an event that must be accompanied by wounds and consistent communication with the roots.

On the one hand, the eight artists of Colorful Korean Painting--with minor differences and exceptions--grew up mastering the grafted grammar within Western art. On the other hand, they all independently digested accepted aesthetics and published originally-cultivated results during the 1980s and 90s. This vital 'sap' sucked up factors of confinement that make up the foundation of our society today. At the base of their aesthetics and form, traces of painful reification, which is more painful than those of acceptance, clearly exist. It reminds me of a verse from the poet Virgil :“Anyone who wants to live out of this forest should take a different path." This is the context that our reading of art history is missing.

Colorful Korean Painting as a Timely Subject

At the foundation of this exhibition, there is another urgent awareness of 'digital monochromization' which is even more threatening. The meaning of 'monochrome' goes beyond the absence of colors other than black, white, and gray, and is also a current state of digital civilization. The decisive condition is 'the clock' of NFT art, which moves seven times faster than that of traditional art. It is the clock to busily cause one art boom or another today, and to turn a child who has just taken their first step into a flying Icarus. In terms of business or marketing, it would be a utopian ecosystem. Nevertheless for art, it's a time of dystopian disaster. What happens when you mathematically convert a seven-time-faster clock within the scope of perception? It can be said that there will be a time difference of approximately 350 years between the events of the 1960s or 1970s and the present. At this point, it is almost impossible to expect even minimal communication, not to mention empathy or solidarity. It is not surprising that memory loss becomes a daily habit. The urged aspiration to devote youth and the artistic soul of the 1970s and 80s has already become forgotten, and so has the history of frustration and overcoming.

But time does not move faster or slower. The order of the rotation and revolution of this planet is firm thus far. However, there are just technologies that make time seem to flow faster and from which sensory and cognitive distortions have resulted. In other words, it is not as if humans in the digital age experience seven times more time or richer lives than before. French Philosopher Yves Michaud appropriately identifies the industrial technology and social mechanisms that make time appear to move fast: "The age of art should be that of events. Something has to happen constantly. But what should happen? However, this question is not a big deal as long as new artists, new exhibitions, open expressions, new emerging themes, etc. are born."

When a number of identical and futile events are arranged at short intervals, the content is not important. It is enough to label the events pouring in day and night as 'new' or 'bizarre' by raking in available resources as if in a war. Global events, art biennales and fairs, various festivals, and new information are steadily produced and circulated. Licensees purging locality busily cross the international date line. Daily guidelines are repeatedly provided. Moral remorse for those who fall behind a seven times faster clock is one of the most important repertoires. It urges awakening and inspires will. The final goal is to hide the violent ideology of the commodity economy and to thwart the idea itself. This is a fascist property of speed.

The analog time of the exhibition Colorful Korean Painting does not trust the technology that Simone Weil cited as one of the three modern monsters, the digital time that flows seven times faster, and the technology that promotes monochromization of thoughts. What the eight worlds gathered here have in common would have been impossible if it had been constantly swept away by a bustling list of empty events every time―events that could easily multiply seven fold.

2. Colorful Spectrum

Hajin Kang – Dongchul Ha: The Source of Color and Light

Given the aesthetic temperament of Koreans, which is extraordinarily emotional, "it is rare to see a world built without owing anything to ‘Fauvism’, ‘Dada’, or 'Art Informel'." This is what Kyungsung Lee said about Dongchul Ha's painting. Even though it's a good observation, it's hard to truly meet people simply by observing. The light that brightens up Ha's paintings is emotional. It is the light "he saw when he was waiting for his mother to return home when young" and "the light of the flower bier associated with the death of his father." It's just a difference in the way he brings it to the surface.

"Draw an invisible world," says Hajin Kang. However, to trust the invisible world as well, the artist should be trustworthy. "Although my thoughts and goals on creation are a little different from his, I have never questioned Kang's work", says Lee Jong-gu. There are three reasons for his belief: authenticity, a competitive attitude, and a deep mind. These hold true value that cannot be embodied in a résumé.

Dongchul Ha's light faces longing and transcendence at its source. For Hajin Kang, color is the product of reification created by the repetition of the act of dotting and erasing. Non-matter touches the material world, and color is derived from the relationship between the earth and the universe.

Bongreal Lee – Jaeho Park: Sensory Filters: From Harmony to Purification

A cotton bud was formed again in Bongreal Lee's painting, where the application of compositional elements and emotional touches had once been abandoned. Didn't Bok-young Kim discuss 'the state of transcendence' in his absence? Lee's sense is revealed when he restrains it, not when he expresses it. When he is not attached to it, but abandons it, his senses would come back as sharp intuition. It's soft 'Art Informel', a sharp absence, and a cotton bud from his hometown. However, that can't be Art Informel, monochrome nor sensory drawing. It's just Bongreal Lee himself.

Jaeho Park's senses head to the maturation of lyricism. By its sensuality, lyricism avoids the trap of ephemeral amusement and is not buried in the notion of deficiency at the same time. Senses are high-quality counterweights that measure exactly the right amount that is needed for the art. In the absence of this, paintings fall into a talkative mouth and a vulgar conceptual play. When attracted by this sense, the painting doesn't have to wander through the inconceivable spirituality or fall into the abyss of unconsciousness, or separately prepare a small incense burner for releasing ideas.

Sangchul Choi – Sufan Oh: Tension Between Meditation and Practicing Asceticism

The trajectory left by the rolling stone overlaps 1,000 times and creates a 'ton'. The artist himself steps way back. It is a nominal intervention. Is it unconscious? Is Jackson Pollock being summoned? No, the more the stone rolls, the clearer the awareness becomes. It's not unconsciousness, but a vivid consciousness. What about John Cage's coincidence? To Choi, the detonator is not a coincidence, but a necessity. Essentially, gravity works on everything. It's a form of resistance not to resist. Sangchul Choi's drawings follow the law of physics and quietly criticize the nonsense of the 'anti-art' of the last century.

The line of Sufan Oh has strength, but its strength comes from free driving without being bound by the object. The mindset is clear but unpredictable. It is not declarative but inclusive. It is an act, but an act of empty desire. 'Emptying' signifies waiting for something. It's taking a stance of "accepting something that passes through the truth, completely naked", and it's a mindless aesthetic (without intention) that becomes a passive voice of its own accord. When the mind is emptied, the soul calms down and the fog of consciousness is lifted. Actions are freed from evanescent functions.

Kang-So Lee – Sun-Cheol Kwun: Brush Strokes as an Aesthetic Vector

In order not to be drown in your senses, you must let the senses flow outward instead of holding onto them. The brush goes as it pleases, but it knows where it must go, like the sea route or the skyway. Instead of loading your mind on the brush, when you dip the brush in your mind, the brush goes only as far as the senses lead. There is a clear mind and energy at the tip of the brush. This is because toxins, burial, attachment, obsession ―produced by remaining― are washed away. Even if you draw a bird or a boat, only half of it is reproduction and the remaining half is expression.

Fate and the whirlwind of history are both depictions of inevitability. Sun-cheol Kwun's painting is a confession about that inevitability. It's his own confession, the people's, and that of the times. Kwun tries to catch what Kang-so Lee lets go. When Lee discusses meta-recognition, Kwun holds the perception of the land. Kang-so Lee refers to painting as an aesthetic equivalent of 'humane life'. Sun-cheol Kwun sees it in "a kind face with a good facial expression." The moral character of the two artists permeates the foundation of the two worlds.