Kho Chunghwan (Art Critic)

There is a mixture of riddle-like mysterious faces and indifferent or thought-castrated gestures...I want to engrave the attachment and longing for life and people that were experienced deeply in an accidental space on one day in the trip, or the afterimage of their hopelessness...Remembering existence, recording that memory, that's the routine. (Artist's concept note)

"Kkotdaji, a male Holstein cow, was separated from his mother three days after birth and raised for meat. He was sold to a fat farm at the age of four months, was raised to full size and slaughtered at the age of two" (2021.8.10.)..."Mr. L's friend, a young man, was sent to the sea in a scrap metal-lined ship. The shipping company made a hasty agreement with the bereaved family, and there was no prosecution investigation" (1988)..."The life was written on the door. We put her on the door, until they brought a little coffin, and I want you to write it down. I wish that you at least write that down. My daughter's name was Katya, Katusenka. She died at the age of seven"... "The unknown dog was buried alive in an empty lot because it was too old and sick. Someone found it and took it to a hospital, but it passed the point of no return in two days" (2020).

"After lunch, the bodies of five cars were buried in the ground. From one of them, a woman holding a baby was thrown away. She was nursing the baby, dying" (1942, Poland)..."John Brown, 59, caucasian, pastor, anti-slavery advocate, hanging" (1859)..."Lee Soo-dan, Japanese military sexual slave in China, forgot all Korean words except her name. She considered the doll she got for a present as a child, and she never again set foot on Korean soil"(2016)..."Sowon, 16-months old, 8 months after she was adopted" (2020)..."Kim Gwi-jung, a college student, was sacrificed from an all-out attack after a thousand shots of tear gas in about 10 minutes" (1991)..."Laika, a stray dog; the first space trip, Sputnik 2, a coffin that travels through space" (1957.11.3.)..."Bars, Lisichika, rocket exploded 28.5 seconds into the launch. Pchyolka, Mushka, spent a day in space and died of spacecraft failure" (December 1, 1960)...Doan Nghia, a six-month-old baby, Binh Hoa, Vietnam" (1966)..."Kurdi" (2012–2015).

There were more than 10 notebooks full of writing, including phrases like "Be dark as soon as possible" that could not be understood at first glance.

Was the name Kkotdaji given by the artist? What happened to Katusenka and his daughter Katya? Also, what happened to Sowon (which means "wish" in Korean), who probably would have been named to make her wish come true, to Laika, the stray dog, and to Binh Hoa and a six-month-old baby Doan Nghia? What about Kurdi? I looked "Kurdi" up on the Internet and found out it referred to a refugee baby. Reading the article made me remember I had read it previously. There are some names and events that I believe I have heard or seen before, and others that I have learned for the first time. One of the examples was Laika, a stray dog that was launched into space on November 4, 1957, along with Sputnik 2, on a one-way spacecraft. It was said that he was a victim of the Cold War era when space competition was fierce. René Girard said that all healthy societies, institutions and countries are built and maintained on the scapegoat system. The fate of the system relies on the ability to pass on, resolve, and calm the potential violence of society by pointing out the right scapegoats at the right time. In modern terms, it can be said that SNS McCarthyism and framing are defined as the nature of the system.

Since the notebook was packed with so many words, the artist added separate post-its on the edge so that specific subject matter could be found right away, with phrases like "hate crimes", "refugees", "labor", "animal poaching", "Indians", and "June in Mokpo". This clearly shows where the artist's work originates from. She said that remembering existence, then recording that memory, that's the routine. This concept applies to history as well. History is often like that, isn't it? It is the work of remembering and recording. And for an artist, the routine is actually work, and therefore art. Through remembering and recording such things, the artist's view of history, life, and art meets at one point. In other words, as the artist's work deals with historical topics while being based on a philosophy of life and everyday emotions, it gains a vivid sense of realism and empathy, reflecting the artist's attitude and position on the art itself.

As is well known, the concept of history includes big history and small history. Additionally, there is a history from above and a history from below. If political history, economic history, and social history belong to the former, life history, folk history, and cultural history belong to the latter. The types of narratives that are covered are also different, and if the great discourse and ideology are the former narrative forms, the latter narrative form is close to that of myths, tales, and folk tales.

In this situation, it is difficult to categorize the artist's narrative to either side. Scale-wise, it is closer to small history, little narratives, and life history that were dedicated to poor, small, tender, and sometimes nameless beings (dead in most cases). However, in terms of content it is her perception on political, economic, and social reality, which is the result of self-reflection on reality. It should be considered as a case where big and small histories meet in an individual who is a concrete being in reality, as it's the result of self-reflection within that reality.

Thus, Park Miwha is interested in the scapegoat of political, economic, and social reality. It could be said that she is honoring, commemorating, remembering, and recording scapegoats through her works. Additionally, through her work she is comforting, pitying, and paying homage to them. The subject of the homage is indiscriminate. There is no distinction or discrimination among people, animals, or plants. It's more like they are all bound together by a sense of oneness, gaining the homogeneity of scapegoats. In the artist's work, dogs, sheep, elk, cats, birds, and humans are not distinguished. Dogs, sheep, elk, cats, and birds have human faces and human facial expressions. Does this mean that I came from nature or does it signify that nature is a mother? The mother holds the dog like a baby (Pieta). The mother is also holding grass (a floral tribute). Pieta and a floral tribute: they both seem to pay homage to the dead. Is it because sympathy, empathy, and therefore the hopelessness and longing attached to the deceased are overflowing?

From some point in the past, the ghost of the Anthropocene started wandering around. I would like to interpret that the enemy of mankind is humanism, that is, human-centrism. I also want to consider that the enemy of mankind is mankind. This may be more like what I don't think it is, but actually what it is. The artist decided to rather remember, record, pity, and pay homage to the deceased instead of sharpening the blade on the enemy. Park's works have compassion that such small and soft things evoke, and the deep longing that the dead evoke. There is a relentless aura in which the fallen baby, the bird with broken wings, the face, the facial expression, the seemingly indifferent face--sad, calm, and inward, the torso without a face, the arms and legs, the lying column, the base missing the column, and the broken window testify in silence.

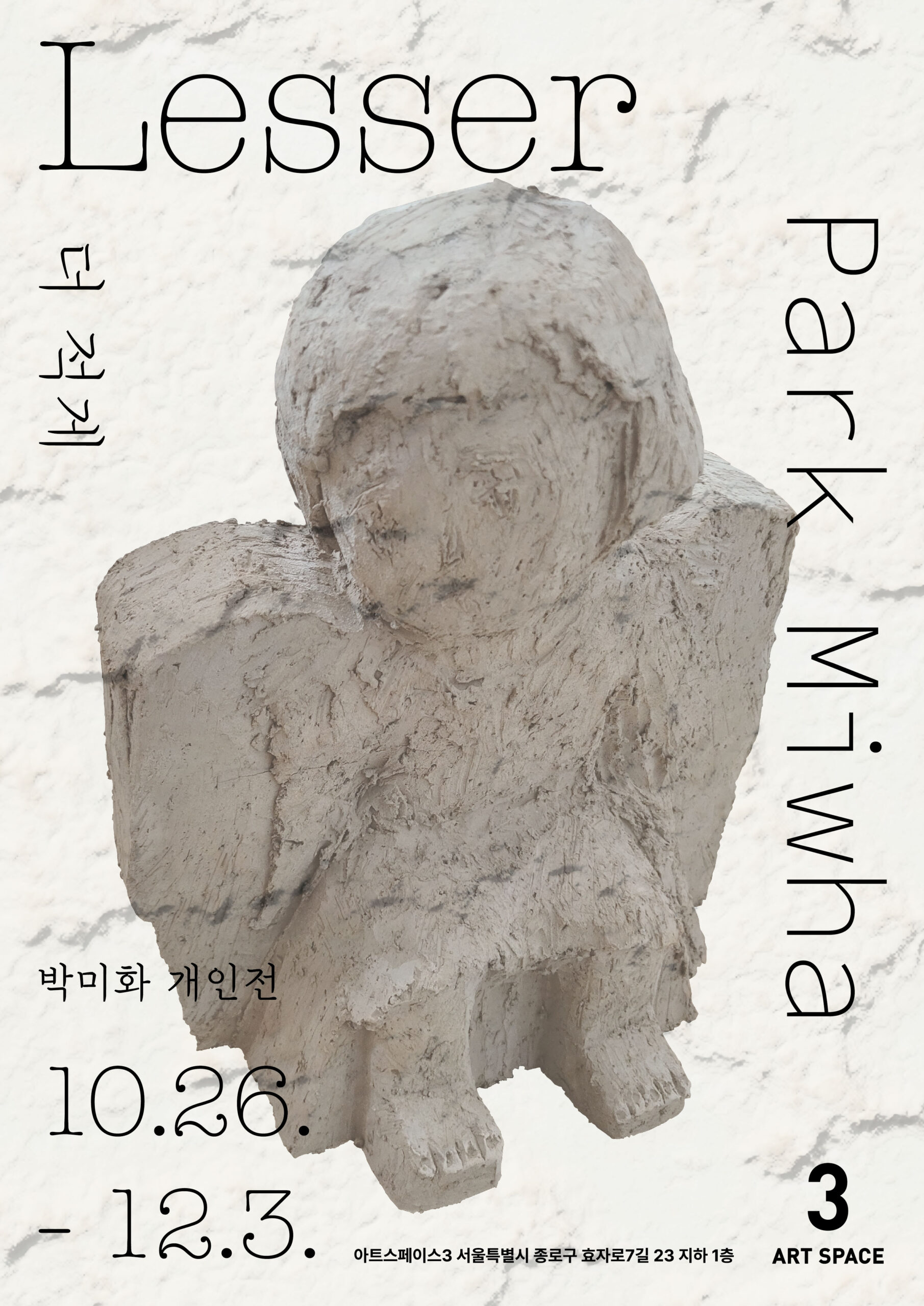

In that way, the artist brings out the words in the notebook (and therefore the stories) one by one and gives them substance. The shape is made from clay, but it is characterized by maintaining the unique shape of a lump of clay by carving it shallowly in bas-relief on the surface, while checking the overall volume and mass. I consider if the expressionless lump may somehow imply a facial expression. It means practicing the theme consciousness of doing less through a lump of clap shaped like an object not fired in the kiln, or maybe it is because she wants to bring out the facial expression of the clay, that is, the nature of the soil itself.

In the history of art, Michelangelo suffered from eidos irony in his later years. He was frustrated by the fact that he had nothing to do (the process of creating is unnecessary) because there was already hidden eidos, a complete figure, in such a material like stone. The artist must have also sensibly recognized the nature of the soil, the eidos of the soil. So, rather than giving it a facial expression, she would have helped the soil realize its own nature. In the artist's recent work, the clay sculptures were able to preserve the unique nature of the clay, and even after the exhibition, it will go back into the container and will be returned to its state of origin, back within the soft clay of earth.

Is it an excessive leap of the imagination if I see an allegory of hopeless beings that came from soil and go back to soil again, through this series of processes? If you think of it as an allegory of a hopeless being, what is worse than soil is ash. She even draws with ash. She uses such hopeless materials that come from soil and go back to soil, or come from ashes and disappear and scatter as a handful of ashes, for drawing and sculptures. From there, we see that hopeless beings transit and sublimate to hopeful beings. We see the paradox of dead things talking, moving and shaking people while communicating.

On the other hand, the words filling the artist's notebook take on another appearance from a series of drawings depicted on newspapers. They were painted over a newspaper, pressed down firmly with a pencil, and engraved again on top with a sharp blade. It is double-pressing and engraving--engraving the meaning of the word--the scar, while recording, writing, and carving with a knife again. Writing is a record and the scar is also a record, but the scar lasts longer than the written word, or put another way, written history. The artist reverses the myth that history often remains, but scars are forgotten over time. Moreover, scars are more vivid, sincere, and deeper than history. History is sometimes suspicious, but engraved scars on the body continue to survive by transferring and transforming themselves to memories, anger, longing, violence, sadness, unconsciousness, other subjects, traces, marks, compassion, signs, symptoms, and mysterious riddles.

Thus, a series of drawings engraved with history, scars, and perhaps the artist's own determination and will gathered in a mosaic of 360 pieces. Some might say that it is an archive work that remembers, records, and commemorates historical reality. They say that it has a monumental character that makes history of small, sensitive, dead, hopeless, and unnamed things. It can also be said that it is another version of the previous series' work consisting of 400 panels that were made with embroidered texts on the cloth one by one, every day for a year and a half from late 2017 to early 2019, as if she were keeping a diary. Due to the nature of the work, it can be said that it is work in the present progressive tense and will continue to be added to, expanded, and varied in the future.

Park Miwha said that she sympathized more when talking about loss than happy stories. Milan Kundera said that the tragedy of modern people's lives is because there is no tragedy. He most likely didn't mean that there is no tragedy, but rather that there is no sense of tragedy. Tragedy purifies life (Aristotle), death cleanses life (Freud). Therefore, perhaps regaining a lost sense of tragedy and death, loss, deficiency and shortage, restoring compassion for existence, and thus welcoming the others (Levinas) can quell the ghost of the Anthropocene. It can save humanity in a grand way.