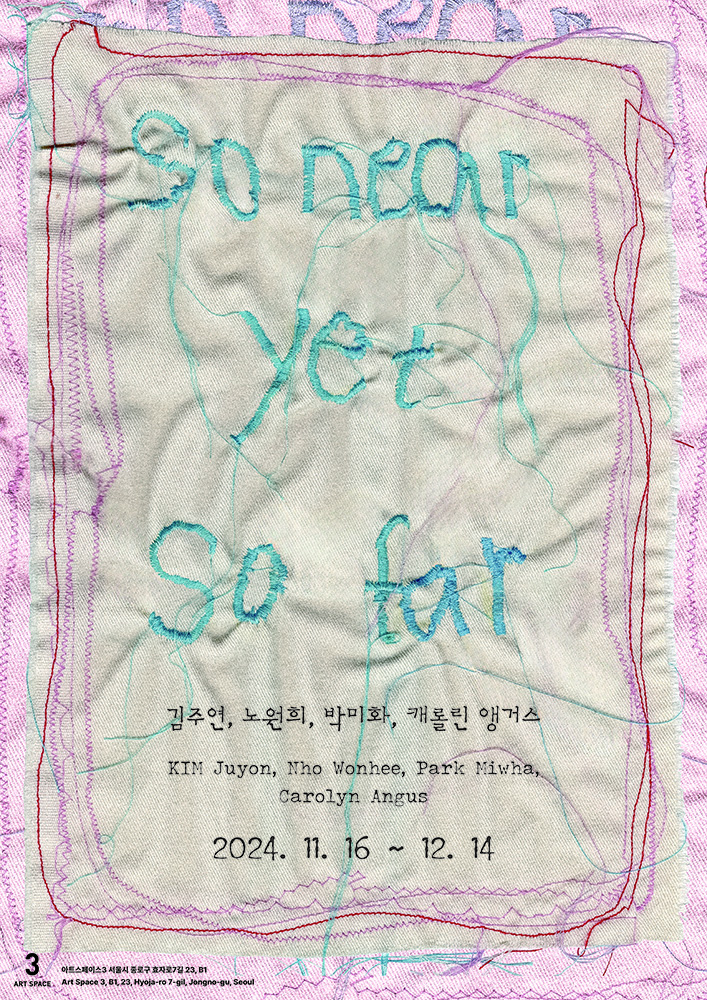

Her, So Near yet So Far

Lee Sun Young (Art Critic)

The four artists participating in this exhibition only have a common ground which is that they are women who have been making artworks for a long time. They are not very close to each other, nor do they use common main media. We may say they do installation-which now has become a vague notion common. Although installation has emerged as an alternative to painting, it has become a flexible bowl containing what artists think just like painting. Nevertheless, what connects their artworks might be in the nature of the subjects. Contemporary subjects are not as solid as it is in modern times. The enunciation of ‘Cogito ergo sum’(Descartes) has now changed into ‘I exist where I don’t exist’(Jacques Lacan). This dramatic flip implies that concepts such as ‘I’, ‘think’, and ‘exist’ never stops to be problematic. Those concepts have been taking center stage for an extremely long time. However, the relationship between center and margin is a dominating concept related to certain regions, class, and sex and it is a historical concept that has changed over time. I ‘other’ instead of ‘I’, ‘action’ instead of ‘think’(if it is too radical, ‘practice’ or ‘performance’), ‘process’ instead of ‘exist’ takes its place, we may say the tide is turning in favor of the artists in this exhibition.

Simple and cautious grammar of theirs is not just a low voice in the margin, but it is the reason why their voice gets powerful. While they don’t manifest themselves forcefully, they are subtle and contain potential energy. According to modern philosophy’s flow, the subject's status has been relativized, and as a result, there was a tendency to eliminate artists’ experiences or lives. Nowadays, it may not be synchronized completely, but isotopic concepts such as form, language, and codes have come forth. This means that even the 19th century’s ‘art for art’s sake’ connotes the subjects’ will to live only for the art. The practical contexts supporting purism as such used to be ignored and it is the point where the socially engaged art criticizes. Women didn’t even have a status to be socially engaged, but they constantly spoke up for themselves and fabrication of the ‘purism’. We have learned from our experience that the subjects who can be ‘pure’ are males. Female’s purity only has been romanticized as an ‘angel in the house’ in pre-Raphaelitic paintings or as a mother of the nation in militarism.

Females who embrace the other inside their body and every artistic creation corresponding to it are essentially connected to ‘something else’. The artworks presented in this exhibition feature a wide scope of ‘the other’ which is so near yet so far, starting from the other inside them to the absolute other. The emphasis on botanical imagery in all four artists reminds us of the web of nature represented by plants. Nature also has been marginalized for a long time and now it has approached close to us through hostile interactions with human beings in the age of climate crisis. Michael Jordan says to the first human being which is hunting and gathering humankind, everything in nature is alive in The Green Mantle. He sees everything around us as part of a vast, ever-changing chain, through which all objects, living and non-living, are connected. Those connections are flexible and artists’ plants are the ‘exterior symbol of the invisible’(Michael Jordan). Of course, these other things also got in the way of their lives as an artist.

However, what renews the art which is emptied by the aesthetic ideology after going beyond the project that purism is infeasible is life, not another kind of art. It is important to look at form when content is depleted and content when form is depleted, for homeopathy begets tautology. Art is driven by absence and deficiency. The works presented in this exhibition is full of sympathy for small and delicate things and this sympathy can be traced back to a mythological archetype or elevated to a social sense. Of course, if life is too harsh, there is no space for it. The artists are middle-class, who went on to higher education from home abroad. The rustic materials and forms of their works were consciously chosen by their later aesthetic and life orientation. But class is a more or less convenient necessary condition for continuing work, not a sufficient condition. Important thing is, as it is in the heart of the art, proper distance. The subtitle of this exhibition ‘so near yet so far’ implies the relationship between the others which is close but distant beings.

It is the fibrous persistence found in the works in this exhibition that sustains the work of these othered individuals in a paradox where the strong are broken and the weak are trampled upon. The botanical images put its roots down in reality and do not stand in monumental form, but are perched on slender supports, thin sheets of paper, sheet music, old clothes, cardboard, or on the chest of a sad woman. Before there were animals, there were plants, and nature was represented by plants. And nature is symbolized by women, as ecofeminism claims. According to Jacques Brosse's Tree Mythology, by exhaling oxygen, they formed the atmosphere, the layer of air we can breathe, and thus made the earth habitable for life. That nature is in total crisis today. Because nature is all connected, the crisis is also holistic. The artists seek to evoke small but large ripples, like the butterfly effect, and through a dialogical imagination with others at the lowest, they show that what is needed in times of crisis is a calm but persistent practice.

Carolyn Angus

The yellow papers seem to be faded over time. The title of the botanical images drawn on them by charcoal are all in the names of the goddesses; Medusa, Pandora and Penelope. In mythological women archetypes of women are contained. According to Robert A. Johnson’s Understanding Feminine Psychology, archetype means “the latent potential of typical human behavior in our inner psychology”. It suggests “as the axis or the system of the crystal decisively influences the shape and features of the crystals although we cannot see them when the mineral crystals are made, human behaviors also follows certain expected patterns.” To the artist, myths are not just simply imaginative old tales, it is a “product of a collective imagination”. Myths “are not created or written by certain individuals, but it is a byproduct of collective experience and imagination across generations and cultures” (Robert Johnson). The artist seeks to put her works in rather more universal context than in individual’s. Also charcoal that the artist uses are ancient material, it informs us that “the huge quantities of coal from the Carboniferous forests of 300 million years ago have been passed down to us today” (Jacques Brosse). Papers are also an ancient medium. Dull colors, unclean outlines and thin materials with overlapping lines give off an antique vibe.

The effect of overlapping has to do with the fact that nature itself is an entity with many layers and textures, and another is that instead of blurring outlines, the illusion of movement is captured. Plants are not static: they leaf out and grow again every year, relying on passing winds and animals to spread their seeds. Medusa, embedded in the mythology of horror, appears to have her tentacles erect, while Penelope and Pandora are rhizomic, with no distinction between up and down. Rhizomic plants are more flexible than arboreal plants. Ghost Trees, which represent each of the goddesses and are mounted on the wall in front of them, create the effect of a two-dimensional image in three dimensions. The images, which look like gathered plants, wrap around the its body on metal supports. Where are you, a work in which plants are drawn on paper and laid on the floor in a circle with a screen that has been made to look like a convex and uneven surface, suggests that the cyclical ecology of plants, which begins again every year, has given humankind the idea of resurrection and regeneration. Scottish artist Carolyn Angus has worked extensively with stone and steel, but as she has got older, she has moved to more flexible materials. However, as the works in this exhibition demonstrate, paper and charcoal are materials with an iron hand in a velvet globe.

Park Miwha

Park Miwha’s work Names looks like an old epitaph, one that would have been written long before the dead were memorialized. The rows of plywood on the wall are sadistically carved with a box knife, and their worn and frayed surfaces make us wonder if they will stand the test of time. It's hard to make out the names, nouns, and verbs the artist calls them, but they are no longer of this world, and most seem to be the victims of violence. The disturbed surface suggests wounds, death, and oblivion. It is the artist's lament for tragedy, where finite lives end in sudden events and disasters. However, these tablets do not completely disappear, but remain in the subconscious, rising to the surface. Park Miwha’s subject matter goes beyond the periods of history to mythology. In her charcoal and acrylic on paperwork, Holding Cactus, a melancholic-looking woman in a thorny crown holds a cactus in her arms. This is a characteristic of the Earth Mother Goddess, who embraces the pain of the earth with her own strength. The title Torch, given to the image of the girl in the middle of the vegetation, is ambiguous. The child, the embodiment of purity, holds a torch in times of trouble. But the flame-shaped twig also evokes sacrifice. The variable installation Fallen Flowers, which includes ceramics, exemplifies Park's technique of sculpting as well as drawing.

Confessing that she is not as good as a painter, she turns her disadvantage into an advantage. The simple drawings on the ceramic textures are what make the narratives inside so compelling. The ‘rustic and mythical’ works are imbued with compassion for weak and fragile beings. It speaks of a mother's love, or a fundamental maternal nature. It is not the ‘perfect woman, the idealized mother figure’ that often appears in psychoanalysis. This ideal is deceptive not only for women but also for men. If Carolyn Angus's language of metaphor is based on Western mythology while Park Miwha's girl figure, represented by the three and four sectioned body, is Korean. Park Miwha, who is also a winner of the Park Sookeun Art Prize, shares a Korean archetype with Park Sookeun. Korea also has mythology. However, rather than invoking a specific deity, the artist connects with the spirit of mythology. According to the aforementioned book Understanding Feminine Psychology, ‘mythology is an ancient mythology that appeared long before the birth of Christian mythology. It is a long oral tradition that was later put down in writing’ and “the more fundamental it is, the more direct and simple it is expressed”. The underlying maternal nature that Park connects to is that ‘only those stories that have universal themes survive to the end.’ Motherhood, whether myth or reality, is ‘something that is recognized as true by all people’ (Robert Johnson).

KIM Juyon

Kim's Hommage a Mother series is a series of collages and drawings on top of sheet music, and is a tribute to her mother, who is close to death. She unraveled her memories of the sound of her mother's piano, who must have been nearly ninety years old. The collages and drawings on the sheet music represent the process of plant seeds spreading. Kim's well-known installations have shown the germination of seeds in the exhibition space. In this work related to memory, the process is illustrated. The analytical representations, such as the womb and spores of plants, are rhythmic like notes in a musical score. There was rhythm in the birth of life. Later, rhythm became our pulse and heartbeat. The balance, order, harmony, wonder, mystery, and vibrancy of life can be played on a piano, which in turn can be translated into a work of art. They are woven into a web like life. The skin-tone color of the screen suggests that these processes are phylogenetic. Metamorphosis X is a reference to Kim's keyword, ‘metamorphosis’, which is well known for her work on growing plants. Plants and metamorphosis are closely related. In The Philosophy of Trees, Robert Dumas talks about the way plants ‘realize their metamorphosis before our eyes’. In Kim's work, transformation spans both life and death.

Stacked in strata on an angled shelf and attached with moss, the work is a naturalization of newspapers, which were synonymous with social communication. The paper, which emerges from fibers, becomes a medium of communication and then returns to nature. The print media, full of characters that announce human identity, is transformed into a mass of matter. It suggests that human history is also part of natural history, and in the short term, it also metaphorises the rapid changes in the media system. The Lightness of Being series is a Kim's way of documenting her installations as photographs. The plants planted on children's clothes grow over a period of time. The combination of the new spring and the children's clothes looks bright, but in reality, some of the plants grow on the clothes and some wither, making her work grotesque. ‘Existence’ is a heavy concept, but the ‘lightness’ that follows it confronts the two faces of life. In The Lightness of Being II, the plants growing on the edges of the red clothes, which are often symbolized as women, speak of the closeness between women and plants. The difference in the size of the clothes in the series suggests that the subject is growing as much as the plant. In The Lightness of Being III, the silhouette of an adult woman's coat is made to appear shrunken, suggesting that it is in the process of peaking and fading.

Nho Wonhee

Wonhee Noh's work, with its dark portrait of our society from the perspective of a mother, goes beyond social condemnation or logical criticism of negative phenomena, and makes the viewer's heart ache. The mother's point of view is effective in that fundamental change is possible only if the heart can be moved. In fact, the mothers of those who die unjustly are often transformed from ordinary mothers into social fighters. Society can never ignore the voice of the victimized mother. But mothers who have raised their children well are ambivalent. According to Nancy Chodorow's The Reproduction of Mothering, ‘the reproduction of women's motherhood is the basis for the reproduction of women's positions and responsibilities within the domestic sphere’; as wives and mothers, women reproduce the male worker physically and psychologically on a daily basis, contributing to the reproduction of the next generation, and thus to the reproduction of capitalist production: ‘the gendered division of labor and women's responsibility for caring for children have been linked to male domination and have produced male domination’. Motherhood has both empowered and hindered women. In Korean society, where the material/spirit divide is severe due to rapid growth, women have reached a crisis point where they are even going on maternity strike. It was women who began to participate in society that modified the conservative motherhood by patriarchal standards.

The series of images, icons and symbols on cloth recalls the cloth that mothers use to wipe their children's tears, tie them in a headband, and sometimes fly as a flag. The series is made with acrylics, color pens, and other materials on cloth measuring 84x84 to 89x89 cm. Recently, the case of a marine who drowned during a search operation in a flood-affected area was systematically distorted by the state, causing public outrage. In particular, the systematic cover-up process by the head of state, which was triggered by the ‘VIP's outrage’, accuses the people's rights of being trampled on by the arbitrariness of the state system. Nho drew images on cloth that evoke the battle between those who want to reveal the truth and those who want to hide it, and installed them in the exhibition space. Through the ‘virtual psychology of the victims,’ Nho imaginatively expresses social events that have caused great impact. The dead have no words, and those who hide behind power have no words either. After the Shipyard Accident, painted with acrylic on canvas, depicts a worker who has become extremely obese due to lack of exercise after an industrial accident. For the artist, who has been working on the theme of the common people as a member of the Reality and Speech group in the 1980s, what will the common people look like in the current reality of 2024, is still a topic that remains relevant to the artist in a world where even progress is out of fashion.