“Then the true poem is no longer the word that captures, the closed space of the telling words, but the breathing intimacy whereby the poet consumes himself in order to augment space and dissipates himself rhythmically: a pure inner burning around nothing.”

- Maurice Blanchot The Space of Literature (1982)

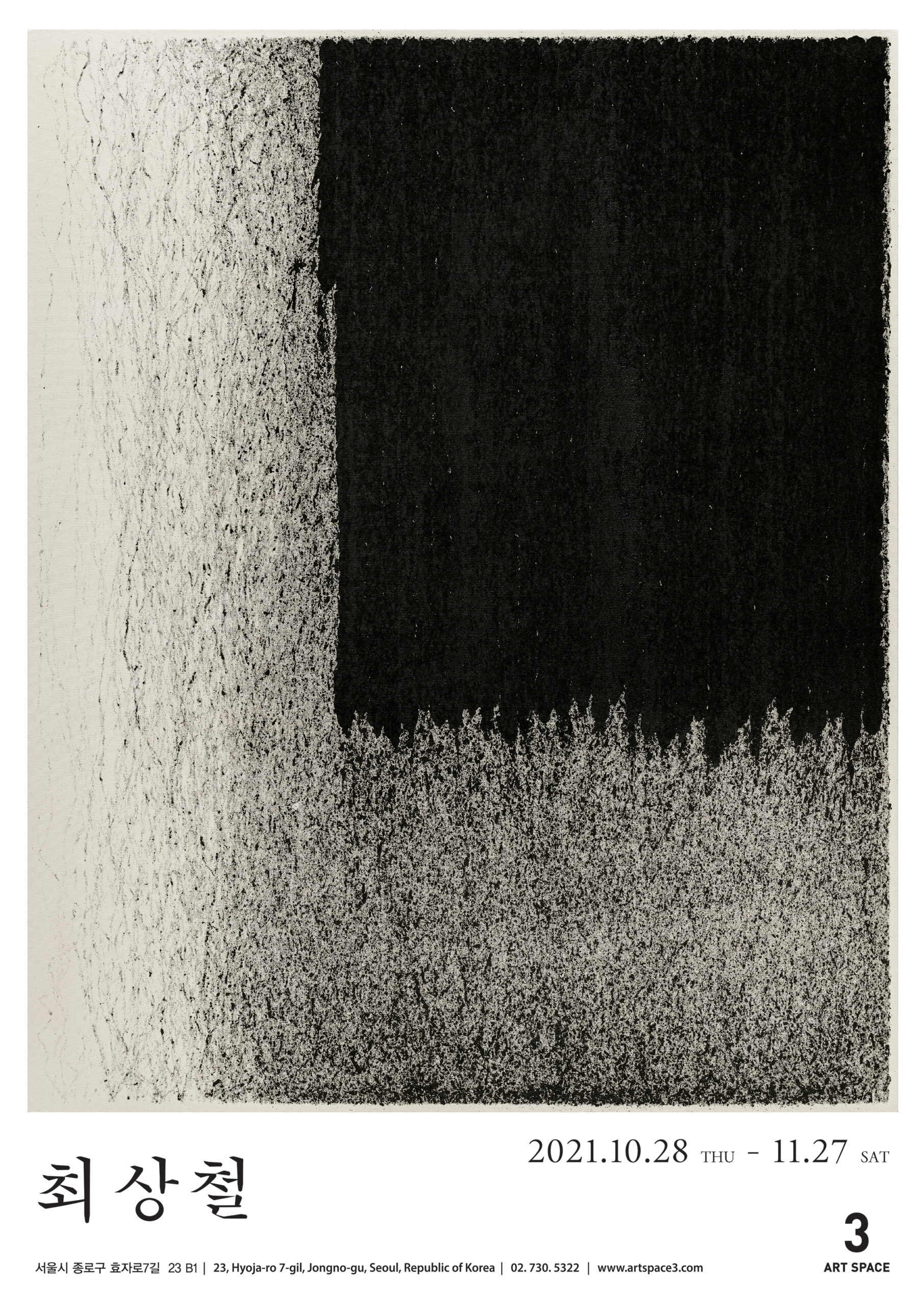

"Thump, thunk, thump." A smooth stone without any angled edges repeatedly bounces and rolls back and forth on the canvas. Only unknown, meaningless sounds fill the studio. Nobody knows when the stone will stop rolling. Choi Sangchul chooses one of the different sizes of stones that can be held in his fist, dips it in black acrylic paint and repeatedly rolls it on the canvas like this. For rolling, the frame that also serves as handles is added on the sides of the canvas. The stone stops rolling around when it's no longer covered with paint. This process could be called the artist's own aesthetic form, but rather, it could be called play under the guise of art. Nevertheless, through such an atypical work process, his own time and space bloom on the canvas. The dialectic of the smudge that accepts the stone's traces while it's rolling and its movement as such, vaguely reminds us what the artist wants to obtain through his work. In comparison, the rolling stone in the time of nature, that is, the absolute time when the sun rises and sets, and the moon appears and fades away, creates relative time and space. One work takes one stone and when a thousand times of rolling is over, the work is completed. The number 1,000 is particularly on our minds, but it is merely a symbol created by the limitations of artificial thinking. For the artist, a thousand times is probably a just number that is neither insufficient nor excessive to finish the work. In short, the artist does not give meaning to numbers. Perhaps escaping meaning is one of the reasons for his work. Welcoming the unpredictable world that follows the law of chance will be the moment of aesthetic impact.

The work begins the moment he places a paint-covered stone on the canvas. The size of the canvas is determined in proportion to the artist's body to permit the best mobility, allowing the stone to draw by moving on the canvas. Choi Sangchul restructures the given format of a painting to suit his body. What's most crucial is that all the work comes from his body. The experiment of modern art also expanded the discourse that the size and characteristics of the canvas are the main elements of painting as well. There are few cases in Korean contemporary art that deal with the relationship between the artist's body and painting. On the contrary, it was often the case that the artist's ego was inflated to build up the work. It is true that the relationship between the canvas and the body is relatively less noticeable because the formless aspect strongly stands out. However, just as minimalist art explored the relationship between space and the body, we should take into account another possibility to observe his art world abundantly. Now let's get back to how he works. Once the size of the canvas is determined, play will soon begin. He follows the law of chance. This is a very elementary and intuitive law that displays the artist's attitude beyond linguistic explanations or meanings. In other words, Choi Sangchul's paintings don't say anything, indicate any objects, nor imply any meaning. Then, questions regarding what paintings should be, and furthermore, what paintings should show, can follow. These aesthetic questions have been a problem post-modern art has faced, and also cause concerns of contemporary art seeking a method between virtual and reality. The resolve to give up the language that expresses art is not just a deterministic act of abandoning the language, but is an extension of the demand to reflect on the purpose of language itself. Paul Klee rediscovered the original form of painting through play. John Cage spotlighted the value of sound that already existed before music. Agnes Martin abandoned her desire for depth and thought of the world exclusively in a vertical and horizontal geometric relationship on a plane through drawing lines. What are these art experiments seeking? They are urging us to explore the essence of art beyond imitation of the world.

Mid-20th century abstract modernism emerged between the collapse and junction of the modern world. Modernism art in Korea was also formed out of a mixture of the ideology, style, substance and spirit of the East and the West within the ideology of the Cold War era, but over time it became a monumental style representing a noble era. Meanwhile, Choi Sangchul devotes himself to the world of silence he chose, distancing himself from the tendency of the art circles. He constantly devises a way of working that is not obsessed with desire for figure or certain visual interpretation, repeating getting away from the frame to be a picture rather than becoming a picture. Describing his way of working as practicing asceticism or seeking the truth is just another cliché reproducing outdated meanings. Perhaps the artist will not be pleased with this expression because he is not creating art to practice asceticism to achieve enlightenment. He is rather going for the thoughts from outside. It is the language from outside and the practice to try to get out of the world that can be depicted in language. That is, there is no difference between painting and writing a poem to him. It's well-known that poetry is not about a form but about a way of thinking. Therefore, for thinking he keeps painting regardless of form. That's how he blocks the chain where mimesis can be reconstructed. According to Deleuze, it could be said that he is drawing a line of flight.

Georges Bataille presented the evolution of humankind as transformation from survival to game, work and then art. Homo Faber, a man who could make tools in the old Stone Age, invented necessary tools out of stones to survive. As the climate gets milder, tools for survival transform to artistic tools to draw. Getting out of the era when survival was the number one priority, humans started a drawing game, containing a magical meaning through images. "Humans whose lives became more peaceful started activities that were not directly linked to work. From this point on, artistic activities were added. The activity called play was added to where only activities useful for survival existed" (George Bataille, Lascaux or the Birth of Art). As you know, play pursues joy regardless of its usefulness. Furthermore, Bataille interprets that the sensory aspects existing between work and tools disappeared as language was being created. In other words, a phenomenon that the sensuous aspect of an object was removed by language took place. Bataille considered that such loss of sensuous matter triggers the need for art. What Bataille thought of as the reason for the existence of art was encounters the world beyond language and the poetic world that regains sensory autonomy beyond consciousness above all. Meanwhile, French philosopher Maurice Blanchot specified poetry as "the open world." The open world is not the place to want something. It's where pure consumption of inner elements happens. Being is exhausted, and everybody knows the truth that this exhaustion is the essence of being. However, the world doesn't consider humans as being, but rather, judges them by social standards. Thus, the basis of being is erased from reality. Therefore, the poetic world of art requests the autonomy of speech. Isn't approaching the very intimate being a poet's activities, that is, an artist's practice? The way to find their own words instead of a language fixed by customs and consciousness is the way to practice art. To Choi Sangchul, work is the process where he approaches the pure consumption of being. Finally, if so, we ask if it is possible to reach a complete abstract. Choi Sangchul's way of working should be counted as an aesthetic method of practicing art as pure consumption and play. Complete abstraction can not be the purpose of work. The important point is to pursue the original form of art, before the distinction between conception and abstraction, that is inartificial, closest to nature like Park Youngtak addressed. Nevertheless, however, the law of chance sometimes seems to be a metaphor or brings up the image of a certain shape. Several works introduced in this exhibition (Mumool 21-6, Mumool 21-7, and Mumool 21-8) remind us of the shape of nature. Shapes that resemble nature or reminiscent of it are eventually a result of coincidence. In short, we have to remember that Choi's paintings are not a completely controlled world, but a world where artists and work or action and results form an autonomous relationship. Above all, appreciation and interpretations should completely be up to those who look at the works. By doing so, the art belongs to nobody with the artist's name removed, and finally belongs to everybody. That's because the autonomy to sense works regardless of the writer's or artist's intention is a right given to everyone.

Jung Hyun (Art criticism, Inha University)